How I Do It

Across all things, begin from first principles, then work from there.

Every business is created in pursuit of a singular objective: to deliver some form of ‘value’ to human beings. This is universally true. When decomposed, the core constituent pieces that make up any business can be thought of as collections of (1) people, (2) policies, (3) processes, and (4) enabling technologies—in that order. These constituent pieces are assembled and carefully coordinated with the expressed aim of reliably, repeatably, and, ideally profitably producing some form of ‘value’ that previously didn’t exist to a human being who is willing to exchange some form of currency for it.

In this case, ‘value’ can be defined as an object (a product) or a process (a service)—or, more commonly, a combination of the two—that affects a given context for that human being. This context is typically predefined in scope, and, when defined effectively, is meaningfully important to this human being—hence the term ‘value’. In order for a business to decide which context they are affecting, to what extent, and how, they must first and foremost understand the human’s mental models and behaviors within said context (whether self-determined or defined for them, as in a business setting). This predetermined psychological state within a given context is what I call human specification. And it is what ultimately decides whether a product, a service, indeed the business itself, succeeds or fails.

If we lead with the context we’re trying to affect, all else becomes obvious.

A context should be thought of as any situation that a human being engages in—we sometimes call these use cases, scenarios, task flows, etc. Whether it’s in their personal life (B2C), or in a professional setting(B2B) it is paramountly important to define the context for the actor (human being) we are affecting. Not just the situation itself, but also their relationship to it, attitudes surrounding it, and any existing beliefs or incentives influencing how they feel about it, how they enter and exit it, and the factors that lead to their performance in this specific context. Defining the context inherently forces us to understand the actor’s mental model around whatever process, idea, or technology we are attempting to change in their life. Whether it be a pain point that individual needs solved—now with a novel fix. A current paradigm in how they think about the world or specific ideas—now altered by your organization’s mission. Or even just getting them hooked on a really entertaining platform or game that kills the free (or not) time that human being previously had on their hands. Every business model depends on organizations first changing a specific context of a human being, in turn leading to a change in their behavior that’s favorable for the business—ideally, in a way that can be easily repeated and monetized. Again, this is universally true.

Even if an organization’s business model is considered B2B, the good or service being delivered is always delivered to a human being, or according to some human’s specific needs—their human specification—in order to solve something for them, in a way they might expect. Tracing the human to the product or service may become more difficult within the complex systems and value streams that exist in B2B models, but it is still universally true that the end ‘value’ always concludes with the changing of some human context. These three pieces of criteria: the human’s needs, why they have these needs, and how they expect those needs to be fulfilled, make up human spec, and should ultimately define a business’s offerings. One of the best rules of thumb in business: If you want to understand what action(s) your business should be taking—and why—you must first start with whom said action would affect, and why.

Through this lens, design thinking becomes a very powerful tool for informing business strategy.

Or organizational problems. Or investment allocation. Even societal-level issues. Starting with the actor(s) we are affecting, the context(s) we are altering, and the human spec that exists within that context inherently forces us to whittle down the universe of possible solutions to the problem in front of us. Regardless of whether I’m working within a product, design, or innovation function, the first question in need of resolution when facing a business problem is:

“What, in our customers’ lives, are we trying to change?”

This is a similar framework to, but distinct from, the traditional Design-Thinking approach of starting by defining the problem in need of solving. I view this approach as superior to the typical Design-Thinking approach because it forces the team to work through what might otherwise be a very opaque or complicated value stream in order to fully understand not only the system of surrounding policies, processes, and technologies that inform the problem but also through the tracing any potential solution’s impact on both business and customer. Also, the reality is that often there may not be a perceived problem that needs solving at all (this is especially true in applied innovation). This additional layer of rigor forces thinking further upstream, and ensures that the team thinks as globally (in scale) as possible when understanding what they’re actually trying to solve for and deliver in the here and now.

Once the initial paramount question is answered, it should be immediately followed up with the following questions that will help us define the complete actor context, along with the underlying human specs we’ll need to adhere to in order to change said context.

“Why are we trying to change this?”

This will provide us a general understanding of the theorized ROI for the organization.

“Is the behavior this leads to currently reliant on an existing solution, process, or mental model that will need to be replaced or outdone?

This gives us a general idea of competitive space and whether it’s even feasible for the organization.

And lastly, but crucially, “How will that actor react/why would they care?”

This forces us to understand the human spec in the situation and align both value proposition and method of delivery to that spec (if a human being doesn’t care about the value your organization is proposing, then you don’t have a business).

This process helps us define the strategy for our action.

This upfront work becomes the rationale for our action, our investment. Not just the rationale for why we’re creating something, but the rationale for why we’re creating the exact thing that we’re creating right now. At the end of the day, what we mean when we say ‘strategy’ is really just a decision, that’s hopefully educated, about what we’re going to do, and how. Everything prior to that decision is research. Everything preceding it is implementation/execution. If we don’t take the time to define the rationale for the decision, then we reduce our investments to a guessing game. Design without strategy is art. Product management without strategy is project management. Innovation without strategy is a very expensive thought exercise.

In the same way that it is universally true that all businesses are complex ecosystems of people, policy, process, and technology, for producing human value, it is also universally true that all action being undertaken within the walls of that business costs the organization money. It’s an impairment on its profitability by way of margin reduction. The reason that policy, process, and technology are all vital pieces of a business is that those structures are intended to reduce the cost of operations. If a business wants to implement them effectively, it’s imperative that its strategy be sound. This is because all of these structures (all structures, really) inside of a business should be shaped and informed by the business’s overarching strategy. If they’re not, they’re just money drains on the organization.

Shipping product without knowing your customers is like proposing to A stranger.

In other words, you’re spending a lot of money on the off chance that whoever happens to receive what you produce will be delighted that it’s exactly what they want, when they want it, how they want it. Business is a game of probabilities. Good strategy improves your odds. And good strategy begins with knowing your target human beings intimately.

Even if you don’t have hard data to educate your reasoning from the outset, the framework above will, at the very least, provide you with more discrete, testable hypotheses that can be validated in cheaper and safer ways than just through shipping software or shifting operations for a service. Your action, therefore, will naturally be coherent from the outset because it is shaped from the very first principles of your (or any) business. Once you take these foundational steps toward understanding your customer, where your business contextually fits in their lives will become immediately obvious. How to provide novel, meaningful, and continuing value will too. But all good thinking and effective action begin with the human your business was built in service of.

Innovation for innovation’s sake is waste of money.

Much ado has been made about the concept of innovation in the last decade. Everyone wants it. Everyone wants to do it. It’s here, and it’s clear, disruption is the new norm. Problem is, not very many people know how to do it. More importantly, when asked, most people can’t even succinctly define innovation. There’s a bit of talk about new technology, as many buzzwords as one can come up with, maybe even some examples. But, when pressed, the definition tends to escape people. This is the problem.

Innovation is a misunderstood term.

Made famous by the tech boom of the 90’s, amplified by charismatic business leaders like Steve Jobs, and understood by almost no one—not even many of the people doing it. What exactly is innovation, anyway?

Innovation, especially applied innovation—especially effective applied innovation—is about solving problems. Solving previously thought unsolvable problems. Solving problems in need of solving for many people, usually utilizing enabling factors (like technology). Usually in order to build a sustainably reliable model for continuing to produce said solution in a (hopefully) profitable way. If, in an existing organization, in a way that is actually achievable. If there is no problem being solved, it’s not innovation. If there is no end-human having something solved for, there is no innovation. If there is no model for reproduction, there won’t be innovation for long. If it’s too costly or hard to pull off, it was never anything beyond an idea in the first place.

To reiterate; innovation is fundamentally four things:

- Solving big problems

- Solving it for humans who deem them important

- Solving it in a way that you’ll hopefully make money from

- Actually getting it done

And I know, I KNOW. I can already hear the rolling of the collective eyes under the jaded eyelids from those who would call this a simplification. They might point to think tanks. To universities like MIT. To places where big minds are getting together to play with the boundaries of technology or culture and creating big, new things that might one day be the next big thing™. But did you catch the operative word in that last statement? It’s ‘might’. Might is a wonderful word. It signals possibilities. It signals to the future. It signals a real value in exploration for explorations’ sake. So why I am I, in turn, signaling to it to imply that it might be the problem with our understanding with innovation (see what I did there)?

It’s because, while ‘might’ may be a wonderful modal verb that can be used to sprout and inspire creativity from great minds, but it is also, fundamentally, a gamble. A gamble that is, most often, difficult to sell. In the world of academia, where the promise of future value—and funding, for that matter—are inherently tied to the expansion of ideas for the sake of expansion of understanding, innovation can be a domain of freedom from constraint (even though we all know there’s never really such thing as a free lunch…ask anyone at MIT).

Talk to any of the actual innovators in the world. They’re all being pressured to chase the dollar sign.

When we talk about applied innovation, the operative word in the moniker is always the former—even though it’s often invisible next to its sexy sibling. Applied innovation is all about innovating within a business context. One that already exists. Think Kodak trying to pivot from physical film prior to their downfall. Unlike the think tanks and university hermitry, the challenge in innovating once an organization is mature lies in the two core facts:

- Disrupting business continuity is expensive (at times even dangerous)

- Pivoting an enterprise takes more than ideas, it takes operational and financial shifts as well

The first should be a no-brainer. Obviously, a business can’t drop everything and chase a new idea simply for the sake of chasing new ideas. Innovation in a business context has the added constraints of the business context around it. That includes how the business actually currently functions. Which segues into the next point…

Pivoting a large business is super hard and expensive.

Even if it’s the right thing to do. Even if it’s in response to an existential threat in the market. Even if the business model for a novel revenue stream seems viable. This is because businesses pour the majority of their money back into their business to stand up functional organizations in order to conduct business more efficiently, improve their business, and/or scale to a wider audience. They bring capable people in, first and foremost, to enable current business. In return, as faithful employees, we get cool things, like paychecks and benefits, sometimes even the option to take time off while continue getting paid. This is all paid for by the existing revenue model (ignoring the market for now, I will write about that at some point too because understanding market pressures on your org is also super helpful).

I cannot express how often this is lost on the teams working inside of any company that is trying to innovate. A good idea is great to have, but it does not inform your Chief Operator on how to move resources and finances to corner an opportunity that may or may not produce future gain. There’s a reason big companies are slow moving (even when it’s actively hurting them). Bureaucracy and conservatism in action are both natural byproducts of an enterprise’s size and position in the market. Internal structures get intentionally more difficult to change in order to reduce risk in someone, somewhere, doing the wrong thing at the wrong time.

While annoying, especially when in a role that is purported to be about innovation and/or change, it’s actually most often a good thing (no, really), as it acts as a self-correcting mechanism for continuing steady state action without costly disruption. Everyone has had an irrational coworker that they can’t stand working with. Imagine if that person was given the keys to the engine that pays your bills. Bureaucracy is the natural stopper for that from happening. It’s real, it can suck, and, unfortunately for the abductive thinker, it is a necessary evil, stifling as it can sometimes be.

So what are we to do? How do we innovate??

There is a solution. And this is where the former term in our moniker of ‘applied innovation’ comes into play. Once we realize that applied innovation is part of a larger system of complex moving parts working in concert to keep the lights on, it is actually deeply freeing. Understanding this allows us to think more broadly about our innovation work, while forcing us to think systematically in how we can work to achieve big things. Solutions must, by nature, include operational tactics and the change management implied by the ideas in order to be considered a full idea. Applied innovation is an operational activity, as much as it is a strategic one.

You need to build an

innovation system before you can innovate.

Applied innovation, as a practice (and functional activity), must inherently include mechanisms for enabling change. If we go back to our Kodak scenario touched on earlier, when digging into the finer details of where innovation truly failed within its context (and I recommend deeper investigation, as it is a fascinating case study), one actually finds that the company had great thinkers internally that produced some of the ideas that would eventually be built by competitors and lead to its downfall in the market much earlier than those competitors formally existed.

What actually led to its downfall was inertia, not the lack of good ideas and ‘mights’. Might is easy. But when your organization is built, intentionally, around a single revenue source, one in which you’ve invested millions into operationally (which isn’t even touching the raw materials part), moving toward an entirely new business idea, that requires different operations, modes of input/output, and (really) types of individuals necessary for realization of said idea, change becomes a much more complex and complicated matter.

The solution lies innovation systems (which I’ll also do a deeper dive around, at some point—promise). If an organization does not take the time to first build a system within their current model that is empowered and representative of the larger whole in both thought and action, the business will not be able to move on an idea, no matter how good it is.

Good innovation practice is, first and foremost, an assumptions testing engine.

This is where we can borrow from other modern practices like design-thinking, product strategy, and modern consulting activities. When building an internal applied innovation engine, a business must root the team in reality. This means not only forcing the team to work through constraints that may seem (and may very well be) insurmountable and, most importantly, experiment at every step of the process in order to prove viability of idea, plan, and action.

This is the crux of good applied innovation. It should be, in large part, a mechanism for identifying, testing, and stressing previously held assumptions by your customer, your market, and most importantly, yourself in pursuit of the next big thing. It needs to have a business model. It needs to have an addressable market. It needs to have a change management plan to get there. Without it, we’re back in ‘might’ land. The land of unconstrained thought that most often doesn’t pay the bills.

Sounds easier said than

done, right?

It doesn’t have to be. But it does take a mindset shift about how we innovate, and why we do it in the first place. It takes the fostering of a mindset of continuous interrogation, good strategy to define the goals and (most importantly) funding source for the innovation work, and, most importantly, understanding the actors affected by the innovation (both external and internal). This takes mental fortitude (especially from leadership), but it also takes an instinct for sniffing out assumptions and perceiving potential pitfalls in the action required down stream of our ideas. It also takes a strong understanding of businesses operate and the real level of effort it takes to get things done.

This is something that VC’s tend to have build a natural strength in, by virtue of what they do. In order to mitigate risk, we must be able to think systematically to define the implications of our idea while at the same time sussing out our assumptions and potential pitfalls that it may produce, or may be hard blockers to even realize it. Easy when it’s your money on the line. Not so easy when it’s the organization’s cash on the line. This is where understanding your organization’s revenue and operating models comes deeply in handy. We must rationalize that the business’s money is, in fact, our money (even if it’s just a paycheck) and not forget that when leaders poke holes in ideas, it’s actually to our benefit that they do so.

Understand the model. Build the system. Focus on feasibility. The money will follow.

Just in the same way that most VC’s become incredibly strong assumption sniffers by putting their own capital on the line, you can also build a strong culture of skepticism by understanding the structures around you and welcome the pokers—they will actually help you strengthen your ideas (not always, but topic for another time). If you can improve this as an individual, and as an organization, you too can build exciting, successful, and lasting innovations for the future. To everyone’s gain.

Product doesn’t have to be hard. But there is a trick to it.

Product Management is two things: Product Strategy and General Management, in that order (it’s not project management, as some would have you believe—but, topic for another time). The first one must be sound in order to do the second effectively. This is universally true. It is also lost on so many organizations. If you don’t have effective—provably effective—product strategy, then deciphering what to manage, how to manage it, and most importantly why, becomes at best, muddy—at worst, impossible. The most troublesome part is, 95{6eb72831712e684880cd3684e48bb75288e121e7c63df2a922850d28c09eb04e} of technology groups out there are guilty of falling into this trap. Why? The reasons are numerous (and I will write about them at some point). But I will focus on the most endemic, as it is precisely what my approach aims to solve.

Product strategy, itself, is not well understood.

A lot of shelf space has been devoted to defining and describing product strategy. What its purpose is, what its consequences are, what good strategy isn’t (so very many in this last category). And yet. There aren’t very many people who can cogently define the term. And many less who can effectively wield it as a practice—in real time.

As sure as the global technology consulting market has continued to steadily increase to the tune of over $200 Billion per year (with product and implementation management at its heart), the Bains and McKinseys of the world have staked their empire on the very provable fact that product strategy, as a practice (and a concept, really) tends to allude even the most impressive MBA’s the Ivy League sees fit to mint. Why? Is product strategy that difficult of a practice to hone? Yes and no.

So what is product strategy?

In order to have a sound understanding of product strategy, one must first have a sound understanding of strategy—which admittedly, not many do. But once we glean the first-principles understanding of the sub-term at the root of the practice, it should be much more obvious what product strategy is.

If strategy is a game of making educated guesses about changes in action to produce a desired result, then product strategy is exactly the same thing, only with a focus on what we should—and, more importantly, what we should not—be building into our product offering (or subset therein). Which sounds easy in theory, but in practice is much more difficult than one can imagine. This is due to the complicated nature of producing desired results in a product context.

Typically, good strategy is defined within the closed system of a business. AKA—what does the business need to happen in order for continued advances in competitive advantage, or, as is more often the case, for a narrowed advancement on local revenue targets. The reason it’s so important to understand this dichotomy is because, for most products (excluding internal enterprise software—to an extent), the true impetus for producing the most common of desired results often doesn’t come from inside the business that is driving the need for changes in a piece of software, or abstract processes that make up a service—it comes from their customer.

The need to understand one’s customer on a psychological level is lost

on most product orgs.

This is where Product tends to clash with Design in most orgs. Questions around who owns what, what decision making falls under whose purview, or whose responsibility it is to be talking to the customer. The reality is that these practices do overlap in very meaningful ways, but it is absolutely imperative for both to understand the human beings that they are in service of in order to understand what they should be creating in the first place. If product doesn’t have a clear enough understanding of the psychological factors that will impact the success of their product (or even nearest-term release), then their set of criterion for what coordinated coherent actions should be taken is deftly incomplete.

You cannot produce business results if you do not understand what changes will enable them in the minds of your customer base. And in order to understand that, you need to actually truly know, and understand them as human beings. Only then can a good strategy be crafted, planned for, and executed against.

So where does general management come in?

Before we define its role in the process, we will first quickly define general management, and why it’s a crucial piece of the puzzle in understanding good product practices. General management, unlike project management, is about managing the disparate moving pieces that make up a defined value stream in order to create reproducible processes that continue to generate desired results for an organization. This means that it is about controlling for factors that sit outside of just one specific function in order to produce success for a given scope of a business.

Think about it: you don’t manage a product—you manage everything around and intersecting with the product. What would it even mean to manage an inanimate object? It’s incoherent. The role of product is to manage against incoherence in action, or in tradeoffs that will be detrimental for the strategy it is in service of. Or, put more simply:

Good product is about the preservation of strategy.

I will be the first to tell you: Setting a strategy is 1 million times easier than preserving the strategy in the face of unforeseen day-to-day challenges and uninformed actors in the executional stream of your org. The role of an effective product manager then, is to set coherent strategy that feeds into the higher order business strategy based on whatever factors may be at play locally (these are internal and external—remember your customers), and then to do whatever necessary to ensure that the intent in the strategy is not lost once something is released into the world. It even extends beyond that, as it is also about measuring whether the strategy was true to its own intent post-release as well.

Of course, this is an endeavor that cannot be completed by a single actor (or contented group of actors), this is a multi-departmental, cross-disciplinary undertaking that needs careful coordination in order to get it right. The product manager is only the steward of this system of moving parts. BUT, in order to be effective, product must be conversant and educated in each of the moving parts in order to ensure they operate correctly (this is a feature, not a bug—although it can also be why most product managers can’t cogently define their role, and why the title tends to be a catch-all for anything that doesn’t have a SME individual filling the process in the company). The emphasis on the second to last word is crucial. Product is fundamentally an operationally-focused management role. Sure, from a strategic standpoint, it must have as wide a lens as possible, but when it comes time to execute, it must be about managing—in the general sense—the action of a defined value stream.

If we understand this, we can craft effective Product.

But only if we understand this. Product management is a concert in three movements. First we strategize, then we plan, then we manage like hell to make sure things go well. If the last part is overlooked, your product, and by extension your business, and by further extension your customers will suffer for it.

Strategy is the least understood, most important, practice in business.

If I had a dollar for every time I’ve heard a strategist incorrectly apply strategy, I’d be a very rich man. I invoke the actor for a very particular reason. It is doubly frustrating to see time and again, people with the word in their titles using it incorrectly—or more damagingly (and exponentially aggravating), ineffectually. I have worked with over 500 companies in my career. One common thread among them: nearly all of them have someone filling a strategic role whom has no real conception of what strategy is, or how they effectively apply it. This sounds like hyperbole. I wish it was.

The hard problem of strategy.

There’s somewhat of a pandemic in the world of business. No one can answer the simple, yet crucial, question: what is strategy? A lot of shelf space has been dedicated to the topic by many great intellectuals and academics (and even past sages like Sun Tzu), but one common theme across much of the literature is that very few, if any, of these texts ever take the time to cogently define, first and foremost, what strategy even is. You’ll find hundreds of books about examples of good strategy, and bad; you’ll find numerous methods and canvases (canvi?) created for the layman to be able to input a discrete set of variables into, in hopes of outputting effective strategies; you’ll find hundreds and hundreds of case studies from some of the most famous achievements and blunders in business; you’ll even find specific step-by-step processes and mental models for how to be more strategic as an individual, acting within a given role.

The problem? They all assume their reader already has some idea of what strategy actually is. That is the deadly assumption (yes—sometimes literally). Unfortunately for those brilliant (and sometimes not-so-brilliant) authors, this is not very often a safe assumption. In fact, I’d make the wager that it’s actually the exception to the rule that their readers actually have a fully defined mental model of what strategy actually is, much less how to think about all of the tools or methods they may be proffering to them. This may sound like a small, solvable problem—but in reality this is actually one of the largest problems in strategy and, I’d argue, in business: no one can define strategy.

You can speak to individuals. Most will express some intangible feeling about what feels good and bad in a strategy. Some will get close in logically deducing the problems. But few, if any, will provide a concise definition of precisely what would constitute good strategy; how one should think about strategy, both in the abstract and physical; or what about the strategy on offer may actually be the facet breaking it. The reason that this is a problem of paramount importance for the practice is that, unlike many other practices in a given organization, strategy is largely dictated by the working mental model of the individual that is undertaking the action of strategy. This is one of the core principles of strategy. It is a mental process, first and foremost.

If the mental model is

broken, then the

strategy will be broken.

Part of what makes strategy so difficult to define is that the process of strategy happens somewhat immaterially. It is, fundamentally, an abductive process that happens in the mind of the person crafting the strategy. It doesn’t happen on a sheet of paper. Nor in a canvas. Nor in a spreadsheet. These are merely artifacts documenting the process. No, it is a mental process. And because it is a mental process, having a clear definition and structure for the mental process actually becomes crucially important for the individual crafting it.

This all probably makes it sound a bit scary, doesn’t it? The scariness of strategy is a problem in its own right that I’ll probably tackle another time however. It is a problem, sure. But it doesn’t have to be. Understanding and defining strategy is crucially important, but that doesn’t mean it has to be overly complex or out of reach for the layman. I truly believe anyone can learn strategy. But it often needs to be simplified before it can be accessible.

So then, what is strategy??

Let’s get down to brass tacks. I’ve described the problem, but the question remains—what is strategy? We don’t want to fall into the same trap that I’ve delineated above, so let’s define it.

Strategy, at its core, is simply this:

The synthesis and reconciliation between the causal factors of what the current reality is, versus what the reality you’re trying to create would be, given a specific set of constraints, against criterion that define success in particular context and time horizon.

To de-academic-jargon-ify it: Strategy is simply the act of making an educated guess about what needs to change in a certain well-understood situation in order to produce desired results in a timely manner, usually through a series of coordinated and logically ordered set of actions.

That’s it. That’s all it is. A delicate dance in four movements:

- Logical Reasoning

- Organization

- Abductive Resolution

- Planning

Or, put more simply; for any given situation:

- What is the truth?

- What are the moving pieces?

- What do we do about it?

- How do we set effective action into motion?

Notice that the action itself is not a part of strategy. This is very important. Most organizations don’t understand this separation. Unable to unwed the concepts, strategy is often short-changed for the sake of getting the action underway.

Fundamentally, strategy is the action of deciding.

These movements function together—in order—for the sake of guiding meaningful action (typically referred to as building leverage). Strategy doesn’t need to be scary. If you understand its core, first principles, then it really just becomes these four actions to the highest rigor possible within a certain time frame such that we can feel confident that we’re deciding on doing the right things, in the right order, at the right time.

When we speak of bad strategy, we are most often speaking about either A) a shortcoming or total lacking of one of these movements, B) an incorrect order of operations, or C) conflating action with strategy itself (this last point being themes common). But if we understand that strategy itself is about actually making the decision itself—about defining and setting intent for action—then it becomes a lot more difficult to mess it up. It also naturally amplifies the importance of decision-making itself. This is why strategy is so important, and why it is so flexible that it can be utilized in almost every functional area within a business—if done correctly, it is traceable downward through an organization. Yes—your business strategy can, and should, inform even the most seemingly innocuous decisions in the weeds of execution.

One quick note: While precise strategy is often reliant on rigorous research, these are two separate practices, and the need for their intercorrelation is actually a product of your organization’s risk tolerance, more than anything else.

The inherent power in strategy is what makes it seem so difficult.

As mentioned, it is largely a mental process. Contrary to popular thought, it’s actually a very creative mental process. Because the second step is all about abduction, or a diverging mental process, strategy, by definition, actually requires a creative mindset. The strategist must inherently imagine what could be in any given situation, given the levers available for pushing/pulling. Moreover, it’s a creative process that’s almost infinitely flexible.

There’s a reason that so many types of strategy exist. Once we understand that it’s a mental process, we can also understand that it doesn’t need to be reserved for the macro-level executive suite, thinking about the overarching business strategy of the org. Every department within an organization can have its own discrete functional strategy. Each individual in that department can have a discrete strategy for the particular initiative they’re working on. This is strategy’s true power. If understood correctly, it is a fractal process. It works at every resolution of the organizational structure. In every single functional practice. The true power of strategy is that, when wielded effectively by an organization, it is also cumulative. Strategies, supported by sub-strategies, supported by sub-sub-strategies. All adding up to make the movements of the organization more compelling and potent.

This power, however is a double edged sword. It’s also what makes strategy so difficult to understand. And why it’s so widely misunderstood. Strategy is not something that’s reserved for the thinking class. It’s not something that only the ‘creatives’ can wield. It’s both logical and creative. And, when proliferated across an organization, and supplied to the general employee-base—along with its right-hand man, empowerment—it can truly be the most effective tool an organization has that can be universally learned and utilized at all levels to produce not just effective action, but cumulatively effective action.

It all adds up.

Yes, strategy can be difficult to understand—and yes, the academic literature doesn’t proffer enough to the general populace in the ways of elucidation. However, that doesn’t mean it has to be a difficult practice. Nor that it is inaccessible from anyone looking to apply its power. There are hundreds of methods and frameworks out there for applying strategy, but if we don’t take the time to understand it from its core principles, then no amount of methodology or robust canvas will move the actor any closer to affecting good strategy.

It’s like my grandfather used to say, “A shovel in the wrong hands becomes a good workout and a day lost.” Breaking it down to first-principles allows us to put that tool to good use.

Design is the most powerful tool your business has.

Design is oft misunderstood. And because it is, many organizations are not fully realizing the true value of what design can deliver for them. There are many reasons for this misunderstanding, but the most obvious stems from the lack of literacy around design as a practice in the practices that surround it within a technology space. Again, this is not the only reason for the misunderstanding, but it is definitely the most endemic and it is the leading cause of money being left on the table by organizations that have design teams, but misapply them.

To be clear, designers themselves have some responsibility to bear in this misunderstanding. While design as a practice is over 200 years old, Experience Design (which is what we usually speak of in a technology context) is still a rather nascent practice that’s only come into its own in formalizing its methods and processes—and really, its own value—within a technology focused business environment. This nascency, while understandable, has unfortunately led to a shoehorning of the practice into the space that seemed like the most obvious, as it quickly presented itself as a source for strictly visual design work for the digital properties that were sprouting in the Dotcom bubble.

To be fair, most organizations have since evolved. The ‘User Experience’ portion of ‘User Experience Design’ has been brought to the forefront more and more as organizations have come to appreciate the larger design process, and its value in the product development lifecycle. That said, design is still mostly relegated to the executional and pre-/post-release stages of said lifecycle even in some of the most mature orgs (topic for another time).

Let’s fast-forward.

It’s the twenty-twenties. Still no flying cars—but it’s undeniable that tech has come a long way. Unfortunately for the industry however, the practices and processes that enable it haven’t really come along for the ride. Many, many organizations are still very much living in the early aughts when it comes to their product development practices. This latency in maturation extends to design. But it doesn’t have to. Somewhere along the way, design (the practice) realized that it was getting left in the dark in certain very important ways throughout the product lifecycle. As sure as a lot of airtime has been wasted on the fact that ‘design doesn’t get a seat at the table’ and/or the ongoing (mostly unspoken) blood-feud between it and product management (the practice) continues to be waged on a daily basis in most orgs.

When viewed solely through the executional lens, it can be a bit hard to rationalize the tensions being had by design. But when viewed properly—I argue—design’s role can be better understood. And its inherent tensions between product and the rest of the organization can also be understood.

Design is a practice in three movements:

-

- Inquiry

- Protocol

- Implementation

This is universally true of all forms of design—and it has been since the inception of design as a process, some 200 years ago. The problem with the practice is that it tends to get mired in its methods and doesn’t often take the time to turn a critical lens on the methodology as a whole. In layman’s terms, the process is essentially a 3 step process involving 1) research, 2) strategy, and 3) execution/creation. Every design process in existence follows this format (although not always in this order).

When understood this way, the inherent tensions built in to the product development process between it and product become more obvious. When two practices that are supposed to work in tandem claim to take ownership over a single part of the process (strategy), roles and responsibilities will always becomes muddied and strained. Of course, this doesn’t need to be the case. But it does need to be understood in order to be resolved.

Design is a fractal problem-solving practice.

Meaning that the process, unlike much of product management, can be scaled to the resolution of the problem. Whether it be figuring out what the macro business strategy should be focusing on for the next ten years, or something as in-the-weeds and seemingly innocuous as what label on a button in a part of a task flow should be. This is not a bug, it’s a feature.

When leveraged properly, design can literally be one of the very strongest problem solving frameworks at your organization’s disposal. This is because, unlike some frameworks adopted and honed by product managers, the process of design can be universally applied. In fact, most large scale innovation practices are just Design at the macro scale.

Unleash your designers, and you unleash design’s power.

It’s for this reason that I take a rather bold stance on design. It’s not a functional portion of the product development process, it, in fact, is the whole. Giving your designers more free reign over not just the product process, but also the business strategy process that feeds into your product strategy (and development, by extension) helps your organization build better products by default. What the industry missed—yes, even design itself—is that the reason design has always wanted a ’seat at the table’ for decision-making is that great products aren’t made on screens or in code. Great products start at the very top of the value stream when decisions on business or product strategy are being made—often in meetings, often in silos, often by genius™ business leaders who think they know and understand everything about their business and its customers.

All businesses are in service of providing value to human beings. The fact of the matter is, the people most often in closest touch with your customers (otherwise known in business-speak as your market), tend to be the design team that either directly advocates for the working mental model of the customer, or actually interacts with them on an ongoing basis. These are the same people who ultimately have direct influence over the way your products and services function. Expanding their remit isn’t just rational, it’s good business.

Let design research become your business intelligence.

Rather than just continually relying on metrics and analytics that may tell you where a problem may lie, but rarely why it exists, leveraging design at the most macro scale becomes a competitive edge in of itself (read: this does not mean that design calls all the shots). Good designers are good communicators. This is because at a certain point in their careers, they realize that their true role is in guiding their peers and stakeholders toward making the best decisions throughout the entire lifecycle of a business’s value stream. Not just when it hits them on the gantt. Organizations coming around to this idea are the ones that are winning in their industries.

So, that’s all good and dandy, but how do we do that?

Simple: By pairing senior level designers with business leaders throughout the lifecycle of an initiative. They can facilitate strategic operations like Design-Thinking™, and provide crucial insights into the customer at critical moments of the decision making process. Experience Research, rather than being viewed as a function that informs merely execution, can become a critical business intelligence function—feeding into and informing strategic action at the highest resolution scale of your org.

If you map the lifecycle of your strategic and executional actions, then finding places for design to inform and facilitate becomes a very simple exercise. The next steps are merely to staff accordingly, reset expectations, and stand up processes that allows design to facilitate your business’s success. Your product, and your customers, will be better off for it.

Everything we do is in service of humans.

We need to understand them to direct our action.

This is an ideology that I fervently believe in. If the past ten to fifteen years have taught us anything, it’s that design has come of age. With more and more companies and organizations adopting design techniques to solve their business problems, it’s clear that the secret’s out about design. More than just creating pretty and delightful things, design is a serious set of techniques that both solve problems and ensure that the right problems are the ones being solved.

It’s a self correcting, human-focused approach to scientific abduction that tells us not only how to solve for specific problems, but also which problems are worth solving. If you understand that all companies are mechanisms for delivering value to people, then you can also understand just how powerful a conduit for identifying exactly what that value is, and how it can be honed to maximum effectiveness. Apart from being an evaluative method for understanding what is and is not working (which is what is typically thought of when design research comes to mind) it’s also a powerful generative mechanism for understanding customers’ (or employees, or users, or constituents) behaviors, pain points, and desires in order to better craft the value that might meet those.

Design informs. Design validates. Design transforms.

When the true value of design is understood by organizations, it’s no wonder that methodologies like design-thinking and its similar ilk would have skyrocketed in popularity over the last few years. Beyond just informing strategy, design also provides fast methods for validation and, most importantly, the means for understanding exactly what needs to be created in order to solve problems or deliver more value. In fact, the lengthy argument often dragged on in comparing strategy and design (a never ending one) often misses the point, in my opinion, largely due to the fact that they are often one and the same, design just taking an extra step into the execution.

Double diamond, lean UX, sequential analysis…

Everything I describe above is moot if one doesn’t know how to actually do design, right? Well, luckily for anyone trying to get into design, the last several years have given rise to a whole compendium of different proprietary and crow-sourced formalized methods for actually executing design, from start to finish. On the most basic side, you have things like Stanford’s Design Thinking methodology, which just takes you through a shallow understanding around some of the mindsets behind design. In the deep end, you have more methodical and complex ways of working like the complete double diamond method or formal acclimated Agile experience design. And of course, somewhere in between, you have things like the much celebrated Lean UX mentality.

While I like to make the argument that the absolute silly amounts of methodologies and processes we come up with in order to express and teach the principles of design, I think it’s mostly a good thing. Any great designer worth their salt will have their own semi-formalized process to produce great design. The fact that so many are being published and shared so prolifically can only mean that the imperative nature of design is being proselytized at a rate never before seen. It also means that design is becoming more accessible. Once a high walled garden ruled only by artistic elites, design has been finally (although against the better wishes of many) been commoditized in such a way that artistic mastery is no longer the main driver of value in it. The secret is finally out that design, much like the scientific method, can be wielded by anyone, as long as they understand the theory, process (whichever they decide to adopt), and value behind it.

The value of design.

As such, it is no wonder that many designer decry the accessibility and further commoditization of design. Many feel that it devalues their roles. And in some cases, where individuals may be hyper-specialized, it is true. However, like any other industry that’s ever existed, there will always be roles that are more valuable than others, as well as fragments of the practice that are more valuable than others. Where once it was all about artistic ability, nowadays the much more difficult portion to adopt in design practice is really around mindset and critical thinking. Having deep empathy for the people you are creating for, figuring out what the best way to create solutions for them might be under specific constraints, and being able to run through this abductive process in our heads in real time in order to produce value (whether it’s business or user) quickly—that’s the value of designers.

We call it strategy because that’s precisely what it is.

I’ll say it outright. Designers are scared of the capital “S” word. And with good reason. For years, many calling themselves strategists have built a large wall around what they consider to be their turf. In most product orgs, this tends to be product management. Despite the prolific proselytization of the value of design over the last decade, there still seems to be a pervasive belief across many industries that design ≠ strategy. To this, I ask a few questions plainly:

- What is strategy?

- What is design?

- What is the difference between them?

- Where does strategy end and design start?

I’ve never heard the same answer twice. It’s true, when design was incepted, it was not exactly viewed as something that required strategic thinking. In fact, from the outside, it wasn’t even clear that much thinking was necessary. It had the glamour of creative aesthetes, and therefore, was mostly relegated as an artistic activity. Free from critical thought. And, most damagingly, effortless for those who possessed a natural talent for art and order.

Flash forward to 2019. Things have changed. The world is now wise to how valuable good design can be for business as a means for self-correcting, strategic future-proofing. And yet. Attitudes still mostly have not. In most tech organizations, there often still exists an uneasy tension between product management and design. Most commonly so, around what the company should be doing, and why.

UX became a field in reaction to poor product management practices.

This is crucial to remember. And often, a good way to dispel the tension in the room between product and design. There is a lot of overlap between product management and experience design as practices. It is only natural that there might be some conflict between the two given their overlapping scope. That said, when push comes to shove and design is interrogated from a critical objective standpoint, design does encapsulate a large portion of strategy. That is not, in good conscience, arguable.

The problem in the comparison is that often the people doing the judging have a misconception around what design is and designers on the other end are often anxious about labeling their work as strategy because they don’t fully understand what strategy is. When whittled down to its core, strategy is really just about setting a North Star, goal, or vision, making a deep analysis of where the organization is currently, figuring out the delta, and then figuring out how to move in the correct direction. The only difference between that process and design is that design takes it a step further and executes on an idea, tool, or service that will bring about the outcome that you’ve set out to create.

In truth, UX is about designing a strategy.

UX is a multi-disciplinary approach to attempt to understand who is interacting with your product (or tool, or experience), in what environment, and how we mold our business objectives around those two things in order to produce positive outcomes for both parties. It’s not about the aesthetics. Yes, they’re still important, but design has come of age. We need to, as designers, recognize the hard, intrinsic business value in our process and outcomes. What that means is that we, as designers, must take a step further into understanding why we are creating what we are creating, for whom, and what impact it may have before we even get into execution and creation at all. That’s how UX wants to be seen.

The delta between a manager and a leader is a enormous.

It’s almost stereotypical to make the comparison between a leader and a manager these days, but it’s also something that I am quite passionate about. Simply managing people does not make one a leader. A leader, by definition, must have followers. The only way to garner followers, especially in intelligent technologists, is to lead by example. And in this regard, I often excel.

I’m a very hands-on leader.

I believe that the day I stop ‘doing’ is the day I stop growing as a practitioner and as a leader. Being out of touch with the execution around the work puts one at risk of running a team like a dictator. On the flip side, being too hands-on makes it hard to actually do the managing aspect. A careful balance of the two is what I strive for. How much is just enough of each? Well, unfortunately there’s no magic bullet or secret formula. It always takes an honest appraisal of the environment, the skill sets within the team, and the gaps therein.

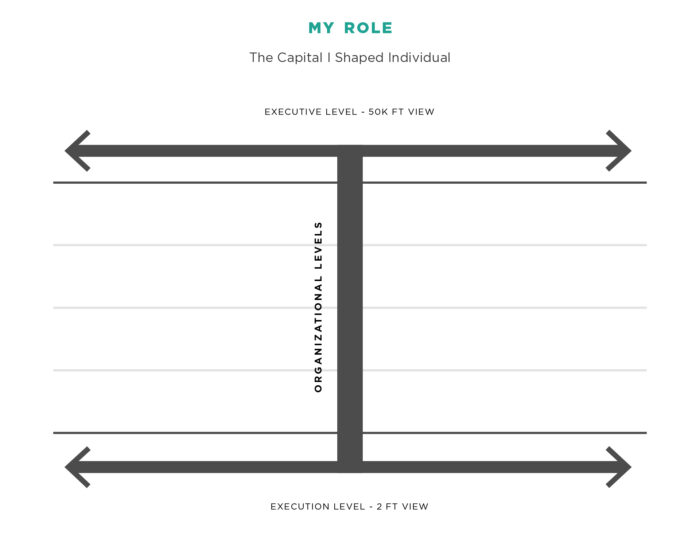

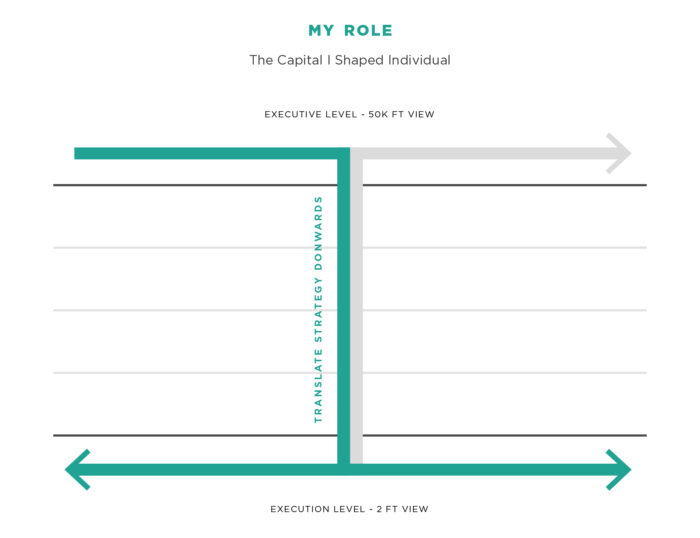

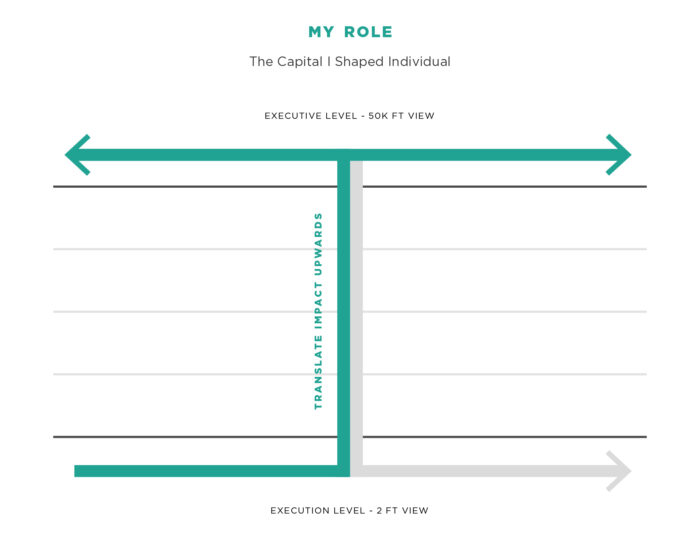

My job as a leader isn’t necessarily to fill the gaps, but more so, to spot them ahead of time, account for them, and orient the team in such a way that they don’t become obstacles or blockers for progress and success. Another stereotypical notion comes to mind about hiring those more talented than yourself—but at the end of the day, I believe in the power of subject matter expertise. I always strive to hire those ’T’ shaped individuals that the industry oft talks about, but aim to create leaders out of them. And that means creating more deep generalists than specialists.

We all carry individual strengths and weaknesses. The only way to overcome the negative is through collaboration.

You could say I am a bit of a process nerd. I think collaboration is one of the most important aspects of a team, but I don’t like taking a shoot-from-the-hip/winging it approach to collaboration. I’ve found this often leads to swirl, bruised egos, and passive aggression within teams. It is often the death knell to small teams that have this modus operandi as it leads to wasted time and effort on projects/work product.

We shouldn’t need to reinvent the wheel every time. There is immense value in having robust processes and agreed upon ways of working within a team: it gives the team a clear starting point every time, adds a level of accountability when roles are tied to activities and gives people an idea of what their day-to-day should look like. Processes should not be immutable, but when a team has a predefined process, it acts as a backbone for them when/if any unforeseen challenges appear. It gives them something to fall back on. And defining it ahead of time gives them the runway to land on, rather than building it as they try to both fly and land the proverbial plane.

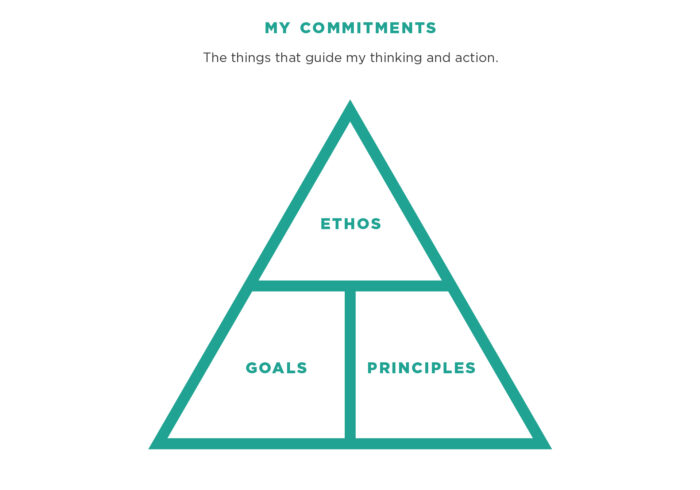

Teams buy into visions of the future, less so into individuals.

While it is impossible to predict every challenge that a team may face, I believe that there are also huge benefits from taking the time to establish what I call the M, V, V’s, and G’s of a team. In establishing the Mission, Vision, Values and Goals of the individual team, it not only makes the team feel like their input matters, it gives them something to be vested in. It stops being just a group of coworkers doing the same thing and starts being a team that is moving towards something. It gives the team a sense of purpose. People like working toward ideals, not toward others’ ideas. This is how I bring the best out of people—by making work something they care about intrinsically, as well as extrinsically.

Experience design—at its core—is a battle against ambiguity.

Good news! It’s 2021! User Experience has been in existence for almost 30 years. And a formal popular practice for at least 10-15. And boy, what a long and crazy road it’s been. From the early days of translating database architecture to information architecture, and eventually into hierarchy and structure, to the Middle Ages of UX (roughly fifteen years ago) where everyone thought UX and UI were synonymous. Yes, a lot has changed since then. Especially in what could be argued as possibly the most relevant of all, the manner in which we go about practicing it.

Experience comes to the foreground.

When the first formal experience designers came into existence, it was a simpler, more nascent time. The web was still in its ‘1.0’ phase, about to move into the ‘2.0’ phase, largely driven by new and more novel ways of interacting with a web page [ahh, the Flash™ days] beyond that of just clicking, type input, and reading (although admittedly, those are still the most common functions). Handheld cell phones were still dumb—despite the world not knowing they were, yet—and most web designers were still designing ‘layouts’ rather than ‘interfaces,’ largely due to the vast migration of folks from print to web at the time. The iPhone was still but a twinkle in Steve Jobs’ eye, and the top dawg in social was still MySpace.

This was the age in which we practiced what I like to call ‘Street UX.’ Because it was still such a nascent field at the time, and many of the standards, methodologies, and best practices we now hold dear were far from being codified and shared out by some of the thinkers in the space. For the most part, a lot of us were just making it up as we went. It probably wasn’t until Jesse James Garrett’s groundbreaking Elements of User Experience that any formal standards or processes entered the collective ethos of the space. After a few more painful years of transition—and several more books on the practice were written by other fellow “Street UXers”—the industry exploded. Suddenly, it seemed, this bunch of ex-traditional-creatives were onto something.

The new era has come and gone.

Flash forward to today. UX, CX, Experience Design—they’re some of the fastest growing fields worldwide, with the US having (collectively) a very formal and mature market for these designers that are going to make every entrepreneur the next fortune through the realization of their dreams. And boy, has the knowledge base exploded. There are a million and one ways to skin the experience design cat these days. We’re awash with methods. And every day we’re still imagining up more and more. All for the sake of having some sort of branded toolkit that we can call our very own.

And why not? Having your own way is certainly better than having no way of doing something. However, in my observation, this growing trend has lead us into dangerous waters. Like many things in technology, it seems that we’re starting to lose sight of the forest for the trees. We’re so focused on the idea of identifying and codifying specific methods for every small portion of the design process that we’ve started to lose focus of what design is and why it is valuable in the first place. While it is quite important to identify and harden ways of executing on the work of design, it’s important for us to zoom out to the macro every now and again in order to remember why we practice design in the first place.

Design is universal. Methods, not so much.

Design, at its core, is an evidence-driven approach to solving complex business and user (or customer, or employee, or constituent) problems. It’s a universal approach to understanding other people well enough in order to solve their problems or offer them some form of compelling value. And that is what we mustn’t lose sight of. While we may have many new methods and ways of working, the process of design (that of defining a problem, creating a vision of the future, then collecting enough data in order to reasonably create a viable solution for it) has not—and really should not—change. While we may continue to part and parcel portions of design into ever more phases and granular methods and sub-methods, but we must not lose sight of the purpose and value of design. It’s the only way to continue to evolve the practice and continue to profligate the value behind it for the future.

We’ll continue to create playbooks and methods, but they’ll be serving a greater purpose.

I believe in an outcome-based process.

Starting with what we are trying to achieve gives us an actionable jumping off point for the project. Everything else is just empathy. What does that mean? When broken down into its essential core pieces, all Design Thinking truly becomes is a framework for establishing understanding the user and the problems they deal with in order to inform whether our proposed solution is the correct one. I think the part that is often left out in the way design thinking is expressed is that empathy needs to extend past just the user.

The most important skill a design or product professional can foster is communication.

I think society (and even we as technologists, sometimes) have this fallacy in their mind for the way that great products and services are made. Some call it the Steve Jobs effect. The genius, in his black turtle neck sweater, hides away in some hidden all-white room and, after being stricken with inspiration creates beautiful innovation, that magically translates to success. All in his little bubble. On his own.

I think it stems from the antiquated idea of what it means to “innovate”. And, really, how software happens. Unfortunately, it’s still largely perpetuated by the agency space in their attempts to commoditize software as ‘project,’ rather than as organic, living ‘products’ that need nurturing and continue to evolve. This is changing. Slowly, but surely, the agency space is starting to see the value in having problem solvers that can actually execute as well.

We must, first and foremost, be problem solvers.

Design Thinking is really just a new label for strategic thinking that must take all parties (stakeholders, team, users) into account. While I do believe it is a simple rebranding of an already existing set of principles that consulting entities have used since the dawn of consulting, it was a very necessary rebrand. For years, the mere term ‘strategy’ was only ever tied to ‘the business’—technologists would hide away in their own space, focused solely on execution.

How do we make more money? How do we move the needle by changing things internally? What moves need to happen organizationally in order for more success to come to the company??? Design Thinking was a way for those outside consulting entities to get the organization to think externally. It’s not all about the ‘you’. It’s about the ‘we’. Design Thinking essentially turns the traditional way of thinking about business problems on its head and allows for innovation and change within an organization to drive value for their customers, rather than focus on tactics that may have worked in the days before or during the early days of the web. Drive value for the customer and success will naturally come.

A design leader must first be an expert practitioner.

We designers are a persnickety bunch. We love judging one another from atop our thinly moated castle we call our ego. We love finding flaws in each others’ work and processes. That’s because we care. We care a lot. About what we do. About why we do it. About why it all matters.

That doesn’t always make us the most welcoming individuals, however. And, from a leadership standpoint, it often makes us difficult to manage. It means that we judge our leadership harshly and often value their technical skills as practitioners over that of their leadership and management skills. It makes sense. We want to work with the best and we want to learn from the best. There pretensions, however imagined or wholly real they may be, unfortunately act as high barrier of entry into design leadership. Understanding the practice from both a macro and a micro perspective seems to be the table-stakes cost of entry into design leadership—so what does it take to be more than just an average leader?

A good design leader is a polymath—

A deep generalist, with expertise in technology, practice, and a wide number of verticals.

A good design director will be the individual who can connect the dots from the overarching business strategy of the entire org, to the individual product or service strategy their team is working on, to the individual chunks of work being executed on by each individual on the team—and be able to articulate it to members at all levels of the organization.

They will be the one who needs to be able to guide and direct the team as necessary whenever any sort of question or issue should arise. They are ultimately accountable for the activities and outputs of the team and need to be able to understand and articulate the ‘why’ behind each of them. They are the the individual the team leans on in order to understand how their individual impact ties to the impact of their peers, their counterparts in other departments, and ultimately, the organization as a whole.

A great design leader creates other leaders.

More than anything however, great design leaders are expert managers, mentors, and coaches. Great design leaders are those that understand that, while their role is important in the design org, they should never become the bottleneck in the value stream of the company, and that designers do their very best work when they are empowered to experiment and learn on their own. They understand that the only way to create a top-tier design organization is through the creation of other leaders through careful and methodical coaching of their resources.

It’s due to this last point that great design leaders are so very difficult to find. Design as a practice, like so many other vocational-type of industries, values the upfront technical skills, but often fails to develop and place value on the more intangible soft and managerial skills that is absolutely crucial in order to be able to lead other finicky, fickle designers. These skills often have to be learned by doing (and failing) and are often glossed over when evaluating potential leaders. It is for this reason that design leaders must work to have defined methods and process for leadership, much as they would for their design process.

The best design leaders are expert communicators and guides for others.

Something that every designer who’s ever worked with me, for me, or just been a peer in the industry has heard me say: “The very best designers are guides.” This is doubly important for any would-be design leaders. I am a fervent believer that what separates managers and leaders is that leaders, by definition, must have followers. They must have individuals that actively believe and support a vision they’ve created for their team or the company they are creating on behalf of. Because designers are so fickle, they often need to have (and be constantly reminded) of the impact their work is making and where that’s ultimately leading the company or product.

It’s this last point that truly separates the best from the pack in design leadership. The very best design leaders must be able to do all of the aforementioned and, on top of that, be able to create a meaningful vision of the future for their team, their counterparts in other departments, and organizational leadership to buy into and invest in (whether that be financially, or just effort and impact). They need to be able to foster a North Star for their team to rally around when times get tough and, ultimately, be able to illustrate and orchestrate the active progress toward that North Star. And that takes great skill in communication and persuasion.

The best leaders are made.

Not in the Mafia sense, more in the human-character sense. Luckily, like most other problems in life, I believe that taking a human-centered, design-oriented approach to design direction and leadership (what is the outcome we’re trying to create, where are we now, what needs to be done in order to get to that outcome) is a powerful method for being able to do all these things that design leaders need to do. Whether it be creating someone’s career track, or delineating how much more evaluative research needs to be done before setting off on execution for the next release of your product, even to building a healthy and motivating culture for the design department as a whole—these are all problems that can be solved with design. And can be taught and learned, by anyone. All that’s necessary, perhaps, is often just a good guide.

The role of applied research: mitigate risk.

This is universally true. It’s really not much more complicated than that. But for some reason, we like to complicate—and overcomplicate–it at almost any given chance. Why? My observation from working with, and building up, hundreds of research teams over my career has been that it’s largely due to the fact that the practice of research is fundamentally misguided in the business context.

When research moved from academia to a business environment, it brought with it many assumptions, practices, and beliefs about the practice, its role, and the processes it holds dear. In the world of academia, research can often be done in service of informing scientific, philosophical, or societal problems/ideas, but may never bear meaningful fruit from its action. Research is seen as a sacred cow that can, and should, be deployed for the sake of exploration. Exploration itself is seen as valuable. Most often this exploration is done in hopes that the researchers might stumble upon something more valuable than the cost of the study itself—usually to add to some larger lexicon of understanding around particular subject areas: the noble goal of exploratory studies in academia.

Spoiler alert: most don’t. This isn’t an obvious fact. We now live in a world where we are constantly bombarded with “study shows this” and “study shows that” headlines 24/7 from any news outlet with access to press releases from the university industrial complex™ wanting to tout any and all studies that may be interesting to the general populace so that they can continue to justify their bulky endowments and the donations from their many alumni. For every study we hear about however, the truth is that there are literally thousands of studies we don’t, that yield absolutely nothing valuable or applicable for the world. There are over 1000 research focused universities in the world, many thousands more that aren’t focused also performing research within their walls. That equates to literally millions of studies happening all at any one time in the world. And most won’t yield much of anything, even in a narrow sense.

Porting research to the business world.

Business is not academia. While there are many similarities between the two worlds, they operate under very different rules, constraints, and pressures. In an efficient business, for example, most management thinkers would say that no system or structure should be superfluous. Every thing must serve a very specific purpose. Reality is nowhere near close to that utopian view of efficiency, but the point stands—all functions, departments, organizations, policies, processes, and even enabling technologies should—in theory—be purposeful, otherwise they’re just overhead. Research is no exception.

And this is where the largest differences in academic and applied research come to play. Unlike in academia, where research for research’s sake is not only allowed, but often encouraged, research in a business context must serve a specific purpose. Regardless of what function applied research (or, research in service of application—or, research in a business context) is in service of within an organization, it’s purpose is singular. That of reducing risk for the organization in its strategy. Meaning that it is in service of ensuring that the two core models that produce financial success—the business model and the operating model; or its value proposition to the market, and the effective delivery of said proposition—are sound from both a thinking and an executional standpoint.

If a study’s value is unclear, your research org is probably misguided in its aim.

Research must be in service of an actionable question. These open questions that come up in business are defined as ‘risk’. We refer to them as ‘risk’ (as a category), because without clear, valid answers to them, we can’t be certain that what we’re doing, from a business sense, is in fact what we should be doing. Therefore, research’s role is in mitigating against this risk. This is universally true. Yes, that is redundant from my exposition, but I repeat it to underscore its importance. I am allergic to the term ‘exploratory research’ in a business context (something that design has come to misguidedly embrace) because the implication is that of the academic sense of research. Meaning that it may or may not yield any meaningful, or actionable data. If ever a study is crafted or conducted within your organization’s [metaphorical—especially now] four walls, then it is a symptom of incoherence in either the purpose or the competency of your research organization.

This sounds harsh, but it’s crucially important. And it’s worth internalizing, both as an organization, and as an actor within its systems. This is especially true because, when approached from an overly academic sense, it can seem like a very complex, inaccessible, or highfalutin practice—which can make it very difficult to detect when either of the two contagions has overtaken, or is central, to the practice in your org. As I stated in my exposition, research doesn’t have to be complicated. But unfortunately for the layman, there are few things that academic personalities take more pleasure in than overcomplicating their subject matter to seem more important (incentives, people, just incentives). This is actually why it’s often the case that the worlds of academia and fast moving tech tend to be somewhat hostile to each other. One is in pursuit of complexity for complexity’s sake, the other is in pursuit of simplicity for the sake of eliminating complexity.

Simplifying research to wield it more effectively.

At its most basic, the process of applied research in business is simply a process of sequential inquiry. It can often be reduced to:

- What are we doing?

- Why are we doing it?

- Are we certain it’s what we should be doing?

- If not, why not?

- What would have to be true in order for us to know that it is what we should be doing?

That’s it. That’s really it. Through this small exercise in sequential analysis, you can build just about any type of research study (or even research practice) in your organization. The beauty of applied research and, complementarily, strategy that either informs or is informed by it, is that they’re largely linear, sequential methods of action that, if done with care, can be honed by just about anyone, in any function, in any business.

The devil in the details.

That. Said. It can feel intimidating. Methods, focus, sample size, insights—these important facets may seem like they’re quite complex or out of reach for the layman, however when it comes to research, it’s imperative that an organization—or at least those overseeing risk management in any capacity—understand these aspects, as they ultimately make or break any risk mitigation efforts within an organization. And I know, even this sounds complex. It doesn’t have to be.

The efficacy of research can be reduced to a few points:

- Risk Areas

- Where does the risk lie?

- The easiest method for sussing out risk when it’s uncertain or opaque is literally just through some proper strategy definition.

- Anywhere we’re making assumptions or where we have old pieces of data that may no longer be true are usually areas of risk in decision making.

- Where does the risk lie?

- Risk Criticality

- How crucial is it that we have certitude on a specific piece of data that will inform our decisions and/or actions?

- This will dictate the methods and sample size (the riskier an assumption or an ‘unknown’ is, the more certitude we’ll look to build)

- How crucial is it that we have certitude on a specific piece of data that will inform our decisions and/or actions?

- Methods

- How are we designing our study to collect data that will inform our action?

- In experience design, we often rely on ethnographic research (which will be the most telling for our target customers’ mental models), but we should never be tied to a single method for the sake of comfortability in the method.